About a month ago, I got my first Raspberry Pi 4.

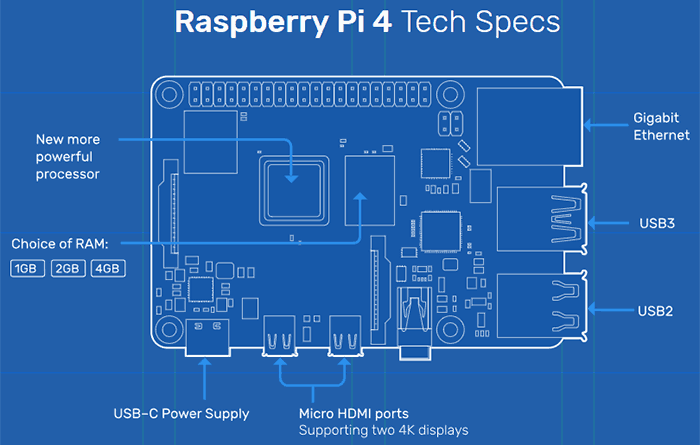

What is a Raspberry Pi? A Raspberry Pi is a small singe-board computer intended for education and for tinkering. For $35, you get a 1.5GHz quad-core ARM processor with 2GB RAM, 2x USB 3.0 ports, 2x USB 2.0 ports, 2x MicroHDMI ports for 2x 4k@60Hz displays, gigabit ethernet, 802.11ac wifi, and Bluetooth. It uses a standard USB-C PD charger as a power supply. All that’s missing is a case, a display cable, and a MicroSD card. Using official sources, another $28. It uses Raspberry Pi OS, a Linux distribution based on Debian.

When my laptop died, I started thinking about replacements and the opportunity to get something to tinker with. I wanted to see just how far low-power computers had come and try to have a fanless computer as my daily machine. If I needed to do “serious work†I could always use it to shell into my larger desktop or a cloud compute node, but I could enjoy pure silence as a default state.

The little machine has exceeded all expectations. It only draws 15W max under load, my usage has been more like 6W. It’s so small, it disappears under my desk with 2 command strips.

Having a small, low-cost, silent computer inspired thoughts of where else a little computer could go. One of the first targets was my astronomy hobby. A modified OS called Astroberry came preconfigured with all the drivers I needed to operate my new astrophotography telescope. I simply bought a second microSD card, flashed it with Astroberry, and within an hour had a full guiding and tracking setup with connections to both my home network and an automatic hotspot for remote control when I’m at a dark sky site.

Working with a new-to-me compute architecture (the RPi4’s ARMv8) and interacting with embedded controllers (the telescope’s PMC-8) has me reflecting on the last time I really got to play with hardware. In undergrad, we learned about embedded controllers with a TI MSP430 retrofitted onto a “Goofy Giggles†toy. A lot of our exercises involved cross-platform compilation of C code from an x86 machine onto the MSP430. It was my first experience with compilation, assembly, and anything resembling electrical engineering. While my machine learning research is beyond abstract, having a foundation in the physical constraints of computation has been incredibly useful.

More important than tinkering or thinking about embedded computing, the Raspberry Pi is a fundamentally democratic platform and that’s where my excitement about the platform is palpable. For many, the Pi could be someone’s first encounter with “free” computing – not in a price sense, but in the sense of freedoms. We live in a world of forced updates and subscription-based software licensing. Our smartphones and tablets drive a consumption-based model of computing. The “smarthome” is just paying money to allow Alexa, Google, and Siri eyes and ears in our most private spaces. Modern software and hardware force us to accept this compromise of privacy and ownership. The notion that we could actually own our software, and moreover, pull back the curtains to figure out how it works is largely lost.

The Raspberry Pi is a different path. I took open hardware running open software and can now control a telescope plus 2 cameras, and do it all from anywhere in the world without ever worrying about my subscription expiring or APIs changing. This is absolutely the future we want, but it’s not the one we’ve been offered by the smarthome. I think the Pi can change this by making computing accessible again, just as the hobbyists found in the 70s and 80s, or how we found as students with “Goofy Giggles”. I’m excited to try as my primary compute platform.